This is a review about ghosts and bitter lessons.

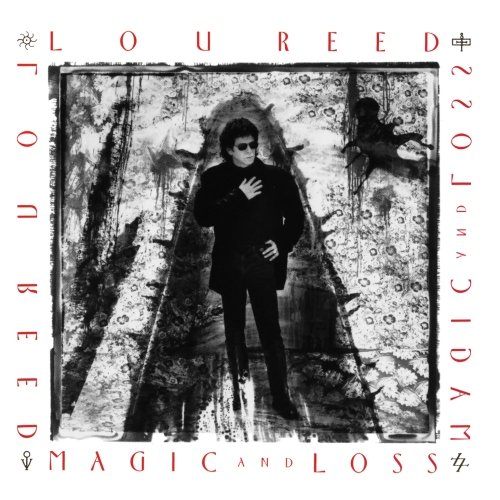

My dad didn’t want to give me the money. I read Rolling Stone’s rave review of Lou Reed’s Magic and Loss and needed the album. It didn’t feel like inchoate longing; this burned like the hottest flame. Reed’s New York album left a mark on me and his solo follow-up demanded a hearing. There’s more though. There’s always more.

I respected Rolling Stone in 1992. The folly of youth. The review described Magic and Loss as a meditation on mortality and blew enough pomp I believed myself lucky to be alive and young for a great artist’s peak.

I begged, pleaded, and promised. He scowled and shook his head until my nudging wore him down. He handed over fifteen dollars and I scurried to Trax Records on Kirkwood Avenue. The album lived up to its billing and I even picked up a later VHS release of Reed and his band performing it in its entirety with Reed reading the lyrics from a lectern. Not very rock and roll, but this wasn’t about rock and roll; instead, it was about great lyrics tackling big themes. I heard it as performed poetry.

I spent the next twelve years drinking with both hands and my dad aged one double quarter pounder at a time. I sobered up at thirty and felt like Rip Van Winkle. I discovered a world perceptibly older than I remembered. The end of things loomed. I lost countless friends or, at least, acquaintances I felt great fondness for. I would now live long enough to see my parents die. I kept coming back to Magic and Loss as a touchstone for the subject and the growing legions of my dead found their way into how I experienced this release.

Magic and Loss seemed to put death in perspective as my dad aged and health problems piled up. Time transformed it into a quasi instructional manual. It became my reference point for dealing with mortality. When my dad underwent a quintuple bypass in the early 2000’s, I decided the album would be what I turned to when I needed to deal with his passing. Lou knew, right? Right.

Lou knew he had something with this album and it still shows. Many of his more tasteful fans heard the verbiage he poured into albums like New York, Songs for Drella, and this album as evidence Reed lost the plot. I heard ambition and those increasingly verbal songs connected with me in a major way, but none more so than Magic and Loss.

The darkly sardonic opener “What’s Good”, the ominous bite of “Sword of Damocles”, and the valedictory air of “Cremation” should move anyone. The poetic sweep of “Power and the Glory” captured the imagination. “Warrior King” and the riff rock of “Gassed and Stoked” explored grief in distinct and memorable ways. Even the spoken word piece, “Harry’s Circumcision”, dug deep enough to expose the same themes of mortality and grappling with our place in this world with tremendous artfulness. The finale and title cut sealed the deal for me. “Magic and Loss” is the clearest personal statement of Reed’s long career and confronts the connection between chaos and creativity while surviving one’s self with a clarity few songwriters could hope to approximate. This sounded like grappling with the gods. Winning seemed immaterial and the reality of a single songwriter attempting to explicate the grave made for bracing listening.

The album followed me through drunken years, sobriety, marriage, and fatherhood. My dad continued to age. I walked to a class on 70’s rock and roll one night when a call came in on my cell. My mother told me he went to the hospital because of chest pains and even had to swallow his nitro pills. Subsequent days revealed his heart giving out on him. They shot dye into his body so surgeons could ascertain the exact nature and locations of his blockage. Kidneys do not like ink. 70+ year old kidneys like it even less. Ink passed through his body without notice before, but at 75 years old, it wrecked him. His kidneys stopped working and fluid built up. One heart attack followed another and my one year old witnessed one. He, eventually, opted for dialysis. It beat opting for certain and near immediate death otherwise.

The inevitable call came sometime before four and five three days after his seventy seventh birthday. I am still dumbfounded I thought enough of Magic and Loss that, on my way out the door of my apartment, I picked up the cd and took it with me. I hit the road, slid the cd in, and drove to the hospital in a daze. The album did not connect. Nothing I heard mattered and seemed paltry in the face of this occasion. Every note sounded hollow and predictable. Music could not match this moment; not Lou Reed, not Dylan, not Black Sabbath, nothing. I reached the hospital and spent over two hours in a room off the emergency area alone with my mother and his body. I had nothing in those moments. Art did not answer. Music had no reply. I sat with my father, John Wayne and Clint Eastwood rolled into one, and there was no song, poetry, or prose capable of flattening my desolation.

I still listen to Magic and Loss occasionally. I still think of that fifteen dollars and a teenage day long ago. I will, however, never believe so fervently again.

Grade: A

Wonderful prose Jason. The power of music weaving into our sub conscious mind and laying dormant like unexploded ordnance.

ReplyDelete