There’s a time when it all comes together for an iconic band, It’s when they reach their peak. They hit their prime. The prime might last for a single album or, more rarely, sustain itself over a string of releases. It invariably comes with youth. It invariably comes in youth. It comes long before cynicism takes hold and the only things about being a rock band that seem real are the money and miles.

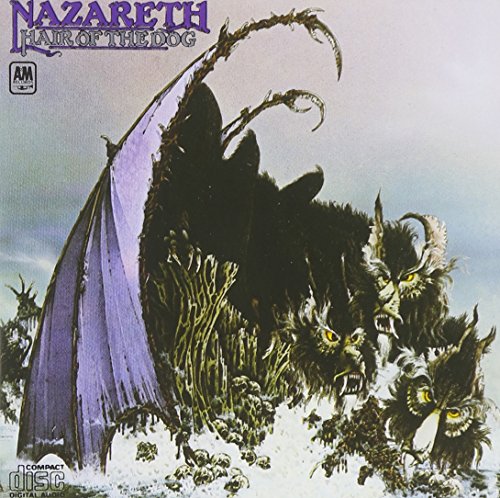

There is near universal consensus that moment came for Nazareth with the 1975 release of their seminal eight song collection (nine in some editions) Hair of the Dog. This review will not debate that point – it’s impossible to quantify artistic achievement. There is no question, however, that Hair of the Dog catapulted the band to a higher level of commercial success, primarily on the back of the smash single “Love Hurts”, than they previously experienced. What is it about this album that sets it apart from earlier fine efforts like Razamanaz or Loud & Proud?

The

focus is stronger here. After navigating their most recent releases with Deep

Purple’s Roger Glover serving as producer, lead guitarist and primary

songwriter Manny Charlton opted to handle producing Hair of the Dog. The

differences are noticeable. Charlton certainly gleaned a great deal of insight

from the band’s time working with Glover, but he clearly favors a much more assertive

presentation for the band whilst retaining an artful tastefulness not always

found on the aforementioned releases. Few portions of the album better

illustrate that than the opening one two punch of the title track and “Miss

Misery”. The former, naturally, became a concert and classic rock radio staple.

It’s taken at a little more of a relaxed paced on the studio recording than the

band served up live; it accentuates drummer Darrell Sweet’s strengths even more

and lends added clarity to Charlton’s guitar work.

“Miss

Misery” succeeds, in no small part, thanks to Charlton’s grinding guitar riff. There’s

more though. Vocalist Dan McCafferty summons up his biggest bucket of blood

blues vocal yet and sets a standard that future progeny like AC/DC’s Brian

Johnson never exceeded. “Love Hurts” set a different standard and, in essence,

birthed a genre – the power ballad. Some might argue it later became an albatross

around the band’s neck with numerous cash-in re-recordings and perfunctory performances, but there’s a measure of genius

in Charlton resurrecting a relatively minor hit from rock and roll’s birth and

recasting it for a shaggy cadre of Scottish blues rockers. My guess is that

Charlton knew what he had with McCafferty when, maybe, his fellow band mates,

including Dan McCafferty himself, didn’t realize it. If there’s a fair

historical accounting ever done for the singers of major 70’s rock bands,

McCafferty deserves a reckoning as one of the best singers from his generation.

“Love Hurts” remains a crowning achievement on his career for good reason.

The

“Black Dog” feel of “Changin’ Times” memorably segues into some straight ahead riffing

that you never find in a Led Zeppelin song. There’s an added element of humor

in this performance that you’d never go looking for from Jimmy Page and

company. Darrell Sweet’s drumming, once again, deserves mention as the

exceptional timing he shows on “Changin’ Times” is no small part of its

success. The band’s cover of the Niles Lofgren penned “Beggar’s Day” is reminiscent

of McCafferty’s vocal on the earlier “Miss Misery”. He’s particularly effective

with Charlton on the bridges leading into each chorus. It’s one of Manny’s best

solos on the album and really fits quite nicely into the song. “Rose in the Heather”

is a brief and keyboard laced interlude between the previous song and the next,

but it isn’t filler. It is, instead, a welcome change of pace and recaptures an

aspect of the band’s spirit we haven’t heard since the band’s first two albums.

“Whiskey

Drinkin’ Woman” scarcely sounds like the same band. This is blues as American

and English musicians of that generation alike seldom understood it. There’s a popular

story of Muddy Waters hearing legendary folk singer Dave Von Ronk performing “Hoochie

Coochie Man: as some scorched earth acoustic blues and breaking out into

laughter. To paraphrase Muddy’s description, Von Ronk didn’t understand that

certain songs are intended to be funny – that sometimes the best way to keep

from crying is to just laugh. Nazareth, unlike many bands of the era, seemed to

understand that about the blues and give us a true original with this song that

embraces the past nonetheless. The closer “Please Don’t Judas Me” runs nearly

ten minutes in length and encompasses everything the band learned over the

process of living, writing, and recording their previous albums. The introduction

of keyboard sounds and orchestration alone qualify this as something much

different from what the band had attempted before. It ends a fine album in just

the right way.

What has been learned? I have an opinion and take eight hundred plus words to explicate it. I believe, however, that if one ear turns to take another listen to this classic, well, beery syllable is worth the struggle.

What has been learned? I have an opinion and take eight hundred plus words to explicate it. I believe, however, that if one ear turns to take another listen to this classic, well, beery syllable is worth the struggle.

Grade:

A+

No comments:

Post a Comment