Nineteen Eighty-Seven was a momentous year in popular music and the world had changed in the two years following Perfect Strangers. On March 9, Irish rockers U2 released The Joshua Tree, the album that solidified their position as a top tier mainstream rock act. On July 21, Guns and Roses released their seminal debut album, Appetite for Destruction. There was a kinetic, aggressive authenticity returning to rock and roll; the theatricality of “hair metal” and 80’s pop was wilting in the face of a gritty return to the first principals of rock music.

Once upon a time, Deep Purple had sounded a similar clarion call that rocked the foundations of popular music. The blistering aural assault of “Speed King” had been a direct challenge to the existing rock status quo and pushed guitar-based popular music into a hitherto unexplored area. In retrospect, it seems safe to say that the Deep Purple that returned in 1985 was not an outfit committed to pushing the boundaries of its sound and songwriting. They were content to revisit past glories on stage and record new material that was often a variation on familiar themes from their past.

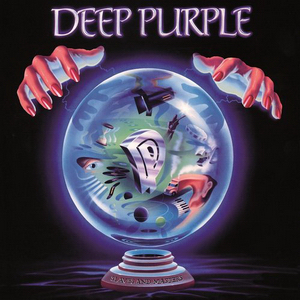

Perfect Strangers played it safe and tried to deliver a solid Deep Purple album with production values relevant to the era. Constructed for maximum commercial impact, “Wasted Sunsets” aimed for the burgeoning AOR market while “Knockin’ at Your Back Door” and “Nobody’s Home” is the duo of hopeful big rock singles. Strongly influenced by the production values of Yes’ recent release, 90125, Deep Purple sounded sonically impressive, but one wishes that they would have possessed more confidence to truly be Deep Purple rather than pandering to the commercial trends of the time.

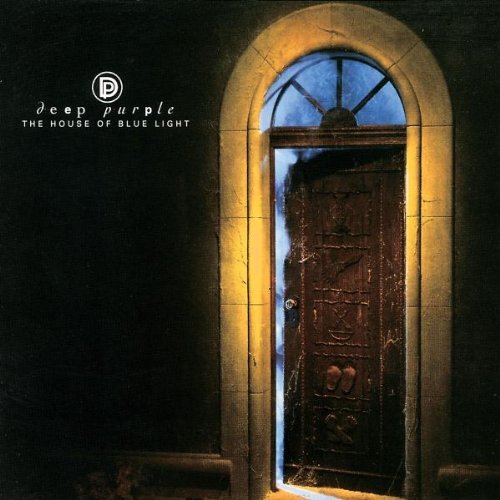

Regarding The House of the Blue Light, there were no promises we would even get a second reunion album, let alone any theories about its potential quality or lack thereof. In a 1987 interview, when confronted by an interviewer who professed surprise that the band recorded a second reunion album, Ritchie Blackmore replied, “After we had recorded the album (Perfect Strangers) many people asked us what we would do next. Everybody thought it was just a one-off thing.”

Sessions for the album commenced on April 12, 1986 in Stowe, Vermont and it took eight months before the album came out. It did not come easily; even without direct references to specific intra-band conflicts, Gillan’s remarks to the press following the album’s release reveal an unpleasant picture of a first class band following apart at the seams. When reviewing each album track for Kerrang!, Gillan dismissed the song “Dead or Alive” as being a “… a pile of shit”. In the same interview, he mentioned hating the riff for “The Unwritten Law” and mocking it behind Blackmore’s back. All was not well for the band’s lead singer. The album’s release faced delays; by September, Roger Glover was at the Union Studios in Munich, Germany, mixing the album, but additional tasks apparently arose. It has been said that Gillan added more vocal tracks and Blackmore later revealed that much of the album had been re-recorded.

Upon release, the reviews from both the mainstream press and Purple faithful alike were unenthusiastic, if not outright dismissive. Everyone expected the mainstream press to thumb their nose at Purple, as always, but despite a strong initial showing on both the US and UK charts, the buzz for the album among fans soon subsided.

The tour opened with three “public rehearsals” in Hungary beginning on January 27, 1987 that were later released in a box set entitled Hungary Days. The template established on the Perfect Strangers tour remained in place; the core Made In Japan set coupled with a selection of new songs. From this album, the band incorporated “The Unwritten Law”, “Dead or Alive”, “Hard Lovin’ Woman”, and “Bad Attitude” into the set, and “Call of the Wild” as an encore in the early shows. “Mad Dog” made exactly one memorable appearance on a later leg of the tour and disappeared. While “Bad Attitude” would disappear and reappear in the set and they would drop "Call of the Wild", the other three songs remained mainstays of the House of the Blue Light tour set list until the end.

While the live performances of these songs are much more successful than their studio counterparts, it remains inexplicable why some promising live songs were passed over in favor of what we were, essentially, clichéd material like “Hard Lovin’ Woman”. Once again, management and market forces were leading the band in the direction of catering towards a specific audience. New, unique material from the band like “Strangeways”, reputedly rehearsed, was lost on any interested concertgoers. Another song like “Mitzi Dupree” could have shared time with “Lazy” in the set list in the same position with entertaining results.

As difficult as the recording sessions had been, the tour fared no better. The band was inconsistent, the sellouts of 1985 were no more and the crowd reaction to the new material was lackluster. The cracks started showing early. On February 20, less than a month after the tour began, Ritchie played “Smoke on the Water” without the rest of the band who refused to play because of a dispute with the tour promoter. A mere seven days later, the roles reversed as the band performed encores of “Smoke on the Water” and “Call of the Wild” without Ritchie in Stockholm. The first foray into America ended abruptly in Phoenix, Arizona on May 30 when Ritchie broke his finger while smashing his guitar. The band would later return to America, but by that point, the bloom was off the rose and any momentum the band possessed had long since disappeared.

In my experience, this album divides the Deep Purple community into two distinct camps. On one side contends that the album is an abysmal failure, an overwrought piece of crap that features tired songwriting, slick 80’s production, and an uninspired band performance, among other grievous flaws. The other camp sees the album as flawed, but not without merit. They assert that the songs for an outstanding follow up are there, songs that, in some ways, are far truer to the spirit of Deep Purple than most of the preceding album.

Well, what of the songs? It is shocking that "Bad Attitude" didn't appear more often considering the live power that the song demonstrates on bootlegs of the era. It is a straight-ahead rocker, the sort that Purple excels at, and Gillan’s vocals on this song were always delivered passionately, if not perfectly, in live performance. It is a complete band performance, even on the weaker studio version. “The Unwritten Law” was a change of pace from the usual Purple fare and an Ian Paice rhythm showcase. “Call of the Wild” is a nadir in the Deep Purple catalog with its crass AOR stylistic touches, clichéd chorus, and dated synthesizer lines. “Mad Dog” is another fine example of Blackmore raiding his own back catalog for ideas, but the execution here is so straightforward, unadorned, and free from trendy production trickery that its power is infectious. The only regrettable lapse is a kitschy keyboard solo from Lord. “Black and White” starts out promising with a wailing harmonica and a brief burst of Blackmore’s guitar, but it sinks into a murky morass of more 80’s production trappings. The redeeming qualities of the song are a strong bridge and the vague hints of an interested Ritchie discernible in the rhythm playing.

“Hard Lovin’ Woman” is a pale imitation of its live counterparts, but it has its moments, especially in the instrumental passages. “The Spanish Archer” is a controversial track from the album that the hardcore Deep Purple fan either loves or disdains; there is no middle ground. It is not a song, per se, but rather an instrumental track serving as a vehicle for Blackmore’s solos. The track is one of the most nakedly emotional tracks of the band’s career and among the finest lyrics Gillan ever wrote for the band. The anguish in Gillan’s vocals charges this lyric about the end of a relationship with real emotional gravity; from the time I first heard this song as a teenager, I’ve always believed that this is one of Purple’s most interesting moments on record. While it certainly is not their best moment, it is a fascinating window into the heart of Ian Gillan as what had begun so spectacularly was now blowing apart in his face.

The vocal harmonies that open “Strangeways” are the first sign that there is some change here. It is a major achievement from the band considering the tenor of their relationship with each other. There is a greater cohesion to this song than many of its counterparts. Each part seems to complement each other rather than sounding like a hodgepodge of musical ideas tacked together and passed off as an organic work of real inspiration. The exotic, slightly alien atmosphere that the band conjures during the instrumental passages is a modern twist to the long established Purple formula.

“Mitzi Dupree” is a spectacular moment on the album that has held a place in my heart over these last 22 years. From the scorching licks that Blackmore offers at the onset, Lord’s wonderful piano, and Gillan’s full on, emotive vocal, it is a brilliant blues pastiche that was thrown together and ended up a happy accident. Some might say that the song is slight and they would be right, but it has humor and is raw and alive.

“Dead or Alive” closes the album with another in an endless array of anti-drug songs that hard rock and heavy metal acts offered during the 1980’s. Even by 1987, the message contained in its lyrics was rote and passé. The song is good, innocuous fun and an up-tempo closer to the album. Purple aren’t giving you anything here that you haven’t heard before, but they deliver it with great gusto; let me caution that statement by saying that if you really want to hear this song, download shows from this era today. However, the studio version does feature a stirring guitar/organ duel that redeems the regrettable inclusion of synthesizers earlier in the song.

Twenty-three years removed from its release, The House of Blue Light has suffered undeserved slights. While the songwriting process certainly suffered from the intra-band tension, the band could still produce flashes of its proud spirit, or provide a reasonable facsimile. These factors, among others, make the album a fractured work. It is, in equal parts, contrived product, an extension of the “safe” approach that the band adopted for Perfect Strangers, a tentative attempt at staking out new approaches for the coming decade, a fond recapitulation of past themes and glories, and overproduced gunk reworked to the tenth degree. Over two decades removed from its release, it remains an essential album for those hungry for a complete picture of this band, good and bad, and who value the legitimate efforts the band has made throughout its career at diversifying its songwriting.

Grade: B